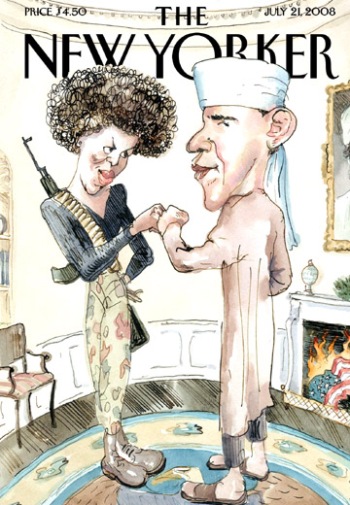

The cover for the July 2008 New Yorker, featured above, depicts a caricature of Barack and Michelle Obama; it’s title – “The Politics of Fear.” The artist, Barry Blitt, intended for the image to be a satirical parody of the Obamas, one that “explicitly takes up and plays upon the larger social text” (100). In this case, the larger social text revolves around the 2008 presidential campaign, during which misinformation regarding the Obamas circulated in an effort to derail their campaign. The image attempts to draw upon this misinformation to expose the ridiculousness of the public’s naivety towards the politics of fear.

Warnick states that, “culturally specific motifs, knowledges, and beliefs provide the intertext that informs the reader’s appreciation and understanding of the intertextually supported text” (96). When this issue of the New Yorker was released, Obama was in the midst of receiving criticism from the misinformation that circulated regarding his cultural background. Paying no attention to his Irish ancestry, Obama’s adversaries used his Kenyan background to make racist accusations concerning his religion as well as his sentiment on terrorism. The image features Obama dressed in a turban, with a portrait of Osama Bin Laden hanging above a fire enveloping an American flag behind him. In viewing these satirical images, the audience is intended to draw upon information they’ve heard in the media in order to interpret the intertextual relations at hand. Juxtaposition is vital to this interpretation.

Porter defines presupposition as a form of intertextuality that “refers to assumptions a text makes about its referent, its readers, and its context” (35). The image above presupposes a cultural comprehension of the politics of fear. Blitt took claims of Obama being unpatriotic and sympathetic towards terrorism and incorporated a portrait of Osama and a burning flag in his image to dramatize them to the fullest extent. His image is a parody, and more importantly a piece of visual rhetoric that aims at exposing the ridiculous scare tactics used to dissuade voters from Obama. Viewers who are aware of these cultural references to the right wing’s criticism of Obama can read the “sociopolitical messages between the lines;” they can construct meaning about the politics of fear from the image because they understand its intertextuality.

However, as Warnick asks: “What role does the originator of the text have in the interpretations of its meaning?” (103). While she states that both producers and readers play a role in the interpretation of meaning, this relationship can only be successful if the audience actually grasps the intertextual references at play. Those members of the audience who fell victim to the Obama rumors may have interpreted the image as a dramatization of fact rather than a parody. Those who do not recognize these sociopolitical allusions have an “oppositional reading” by default, inherently reading the text’s code as literal rather than satirical. Thus, looking back to Warner and Jenkins, it is apparent once again that the public must actively participate in the media in order to grasp intertextually based works such as this one.